Major problems in Los Angeles, the Suez Canal and now Yantian have been massively disruptive to global supply chains but lesser widespread congestion should not be overlooked.

Yantian, one of China’s busiest ports, stopped accepting new export containers in late-May because of a Covid-19 outbreak. Initially this was supposed to be only a few days out of action, but the partial shutdown has dragged on into late June. The port is a major export hub for multiple large markets in Europe, North America, Central and South America and Australasia. The ripples of rerouting and diverting ships has spread to other ports and added to congestion and delays. As it took several weeks for ship schedules and supply chains to recover from the Suez Canal incident, the backlog of cargo in southern China may take months to clear.

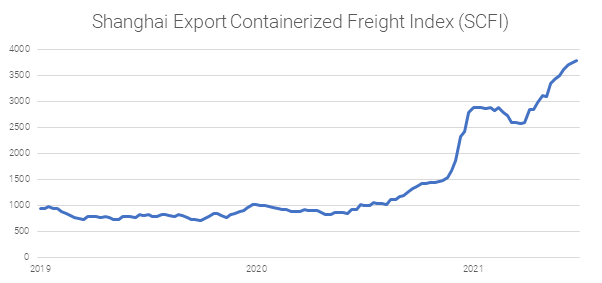

Record freight rates continue to plague global commerce and even without canal blockages and port backlogs the global freight system is largely at capacity. Exports from Asia are at a record high and despite the pandemic cross-pacific trade is still at historically high levels as European economies reopen.

Ocean carriers are deploying most of the capacity towards the U.S. West Coast routing where complexities in the interior of the U.S. (lack of chassis and rail congestion) are slowing operations at port. Chronic congestion in Asia is causing vessel diversions to neighbouring ports, reducing freight handling efficiency, circulation of equipment, and increasing blanked sailings at a period of intense demand. Across Northern Europe congested box terminals are leading to more vessel diversions and carriers unloading cargo at alternative ports with shippers often bearing the responsibility for inland on-carriage or relay. Meanwhile in New Zealand exports are being pushed to airfreight following congestion at Auckland ports, lack of reefer plugs in Yantian, and profitability in empty boxes returning to China intensifying issues (Loadstar).

Container rates for exports from China are far ahead of return prices as a shortage of containers in Asia continues. The effect of the pandemic on trade was relatively short and sharp. Following a steep decline, trade picked up quickly in the latter half of 2020. Responding to the upturn carriers started making return journeys to China empty rather than spending time picking up vacant boxes. This led to full container yards in congested European and North American ports and a shortage of vacant boxes in Asia and the resulting exorbitant freight rates. Read more in our previous blog post.

Since 2018 the shipping industry has been cutting back on investment in response to traffic stagnation from USA-China trade wars. However the high freight rates have encouraged operators to invest in new builds with the global containership orderbook nearing 20% of the active fleet (Loadstar). Nothing can compare to the scale of containerships for goods carried with mainline operators increasingly in the market for Ultra Large Container Ships. Evergreen expects delivery of 34 new vessels between 2021 and 2026 of which 10 ships are 23,000 TEU and Japan-based ONE has also announced plans for the long-term charter of six ULCS with capacity of more than 24,000 TEU (gCaptain). These massive vessels will likely mean additional investment in larger berths and cranes.

Ocean freight being more expensive than ever is a drag on commerce and a potential accelerant for inflation as supply fails to keep pace with demand. The high rates are expected to continue until the second half of the year and until demand levels it is unlikely that congestion will ease. However, delivery of new tonnage across all container stock sizes in the latter half will reduce dwell times and much needed capital expenditure in new vessel orders coming on-stream in 2023-24 will increase fleet capacity. Following this frenzy of shipbuilding and capital expenditure we may even face a glut of container capacity as seen in 2016. The shipping industry will normalise with time, but we cannot expect a big ship to turn quickly.